Ways of knowing redux …

Big Data, data-driven research, machine learning & AI

I recently came upon an interesting opinion paper from Eren and Banfield (2024) on Modern Microbiology – what particularly got me thinking was the last section. “A Shifting Mindset … .” This was a version of Anderson’s 2008 WIRED article -- ‘With enough data, the numbers speak for themselves, correlation replaces causation, and science can advance even without coherent models or unified theories’.

The philosophy underlying this is very timely as Artificial Intelligence has been much in the news with the Nobel Prize in Physics awarded for artificial neural networks and half the Prize in Chemistry awarded to the developers of Alpha Fold 2 which has solved the protein folding problem.

Eren and Banfield’s section is not quite at the extreme of Anderson’s statement but they do say with respect to environmental microbiology: “we advocate increasingly deploying the methods of microbiology* in the context of ecosystems … and explore open-mindedly, and dare we say it, without asking for or testing any strict hypotheses.”

* by which they mean “molecular sequencers, mass spectrometers, high-throughput cultivation, genetic manipulation, and a large arsenal of ‘omics strategies”

If they are talking about the discovery of untapped diversity (whether it be organisms or genes), I have no quibble at all. If they are talking about microbial ecology, then I will differ – microbial ecosystems feature nonlinear dynamics, which present significant technical issues to the underlying premises of Big Data analysis.

Several thoughts that came to mind:

The field of microbial ecology is pretty much at the state of “without asking for or testing any strict hypotheses.” Prosser (2020) found that about 90 of 100 papers in the leading microbial ecology journals approximately 90% of papers in major microbial ecology journals had neither a scientific aim nor addressed a scientific question via a hypothesis. He then commented: “The real limitation to our understanding of microbial ecology lies, not in a lack of techniques, but in a lack of motivation, enthusiasm, desire and courage to identify and ask significant scientific questions in advance of experimental work, and a lack of testable hypotheses and theory, i.e. lack of adoption of the basic scientific method.”

Can / will the analytical techniques of Big Data rescue microbial ecology and answer some of its Big Questions in a hypothesis-free manner? These developments are interesting as they take us back to pre-20th C philosophy of science, to the times of Bacon and Newton ('Hypotheses non fingo'). Big Data science renews the primacy of inductive reasoning. Its “cleverness” arises not from the design of the experiment, but from the capacity of tools such as elementary statistical analysis, expert systems, machine learning, or most recently “deep” learning to identify patterns in data. And indeed, analyzing vast volumes of data can yield novel and often surprising correlations. What remains up for debate is whether this data-driven approach is itself a mode of knowledge production or does it serve as a hypothesis-generating exercise to identify potentially useful information, that must then be turned into knowledge by the 20th C hypothetico-deductive method.

In other words, framing Big Data as induction as opposed to deduction, driven by data not hypothesis and carried out by machines not humans does a disservice to the scientific enterprise. Data-driven inductive phases can be of value early in a research program to generate hypotheses and to eliminate less probable ones, in the spirit of strong inference (Platt, 1964). But deductive phases are necessary for knowledge acquisition.

The story of Alpha Fold

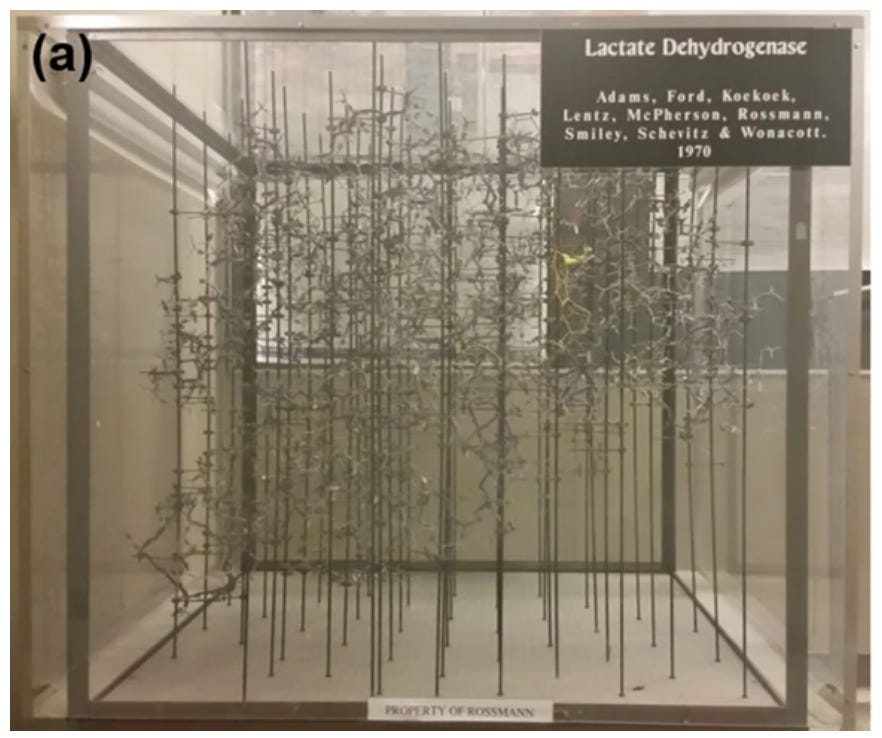

I am in no way a structural biologist, but I was structural biology-adjacent. When I took up a faculty position at Purdue University in the late 1970s, my lab was in the basement of Lilly Hall and I could see Michael Rossman physically working on his 3-D wire models of proteins (NB: no computer graphics then!).

Over the subsequent decades, advances in tools such as computing power, computer graphics and cryo-electron microscopy totally transformed the field. A key objective was the protein-folding problem: predicting a polypeptide’s three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence. Alpha Fold 2 has now solved that problem, and its basis is relevant to thinking about how machine learning might (or might not) impact microbial ecology.

Alpha Fold 2 uses multiple sequence alignments to find amino acid sequences similar to the query, extracts the information using an ‘evoformer’ neural network, and passes that information to another ‘structure’ neural network. There were several key features to its development:

• The superb software engineering – the engineers use of neural network ‘transformers’ in an iterative fashion that included an attention matrix. But that alone was not enough.

• The use of an attention matrix has a quadratic memory cost. So, the massive computing power put to the task, beyond the capacity of academic researchers, was critical. Google DeepMind, said they had used “128 TPUv3 cores or roughly equivalent to ~100-200 GPUs.” But that also was not enough.

• The incorporation of a ‘bespoke’ model (AlQuraishi and Sorger, 2021) that included well-understood chemical and physical features of polypeptide chains. This constrains the space of possible structures and hence makes solution more tractable. Examples in Alpha Fold 2 are that bond lengths are well-known (as are the range of possible bond angles) and that interactions within the polypeptide chain are rotationally and translationally invariant. These additions had important effects on the efficiency and accuracy of machine learning.

Machine Learning / AI for nonlinear dynamic systems (aka microbial ecosystems)

The last point on the incorporation of prior information is key for applying deep learning to microbial ecology. What are analogous sets of prior information for microbial communities? These would need be in the domains of patterns, physico-chemical or mechanistic properties, and experimental / data acquisition error estimators. I would argue that our knowledge in microbial ecology is much poorer than what had been learned over 70 years in studying the characteristics of polypeptide chains.

A first question to ask in any investigation is whether machine learning techniques are needed or appropriate. Walsh et al. (2023) have provided an overview and practical advice. There are a broad variety of multivariate statistical analyses short of machine learning that have been applied to censuses of microbial community composition (Buttigieg and Ramette, 2014)

A cause for concern in the application of deep learning techniques are the complex population dynamics found within microbial (and macrobe) communities. This arises from both empirical observations and theoretical analyses (May, 2001). Their nonlinear dynamics can result in temporal changes that range from damped oscillations to chaotic behavior.

These behaviors cause several problems for “big data” (Succi and Coveney, 2019).

In complex systems, variables (e.g., population sizes of individual taxa) are correlated – extreme values are much more frequent than when uncorrelated and hence do not obey Gaussian statistics (the mean and variance alone do not capture the phenomena). Mo’ mo’ data tend not to appreciably help the system resolve to zero uncertainty as in a Gaussian world.

The collection of quantitative environmental data (both microbial sequences and physical-chemical factors) is rife with inaccuracies, for a variety of technical and operational reasons. The objective of Big Data analytical techniques is to identify patterns, and neural nets do so by adjusting weights of connections in order to minimize the error function. If the error landscape is smooth, this works robustly and effectively (see a). However, if the connections between input and output have features such as in (b), the neural network will produce a solution but this will fail when confronted with a new data set in which it must extrapolate rather than interpolate.

Machine learning produces correlations – the trick is to figure out which are meaningful (causal) connections and which are spurious. Calude & Longo (2018) demonstrated that the ratio of meaningful to spurious correlations decreases steeply as data size increases.

Where is microbial ecology heading?

Will machine learning techniques impact microbial ecology? I have no doubt that it will, particularly as algorithms improve and experience is gained regarding its appropriate deployment. In terms of knowledge generation, a significant problem with deep learning is that it ‘works’ by developing a very large number of learned parameters but these have no physical, chemical, or biological meaning (that is, they do not illustrate mechanism). But it is ‘how’ and ‘why’ that is the goal of scientific research. We search for (relatively) general principles, not just the predictions at which machine learning is proficient . As in the case of Alpha Fold 2, incorporating real principles in the model can not only improve its performance, but may eventually suggest tangible hypotheses that can lead to improved mechanistic understanding.

I think carrying out research programs by intentionally forgoing thoughts regarding hypothesized mechanisms is a mistake and at variance with the history of science. “Science” is not about the random collection of data. Experiments can be thoughtfully designed and carried out in light of a current theoretical paradigm, informed experimental manipulations or selection of sites for ‘natural experiments.’ Modern experimental methods appropriate to the question can be chosen. And the extent of replication and data analytics for the dataset should be chosen at initiation of the experiment. Preregistration of a research study provides a means to thoughtfully carry out this process (Nosek et al., 2018)

The two best-known 20th C philosophers of science provided rationales for this type of discipline. Karl Popper believed that even tentative hypotheses function as useful conjectures that can be tested empirically. Thomas Kuhn pointed to the importance of experimental ‘anomalies’ that vary from our articulated expectations. It isn’t just that the numbers don’t fit – they demand a reassessment of how we believe the system operates.

Eren and Banfield end their article with: “In a world of unknowns, rigorous exploratory research provides the basis for hypothesis-driven research.” I agree that is a valid means to work toward scientific progress, and data-driven exercises are warranted particularly in the earliest phase of a truly novel system, such as the acidic drainage at Richmond Mine studied by Banfield and her colleagues. But if I look at the arc of research in microbial ecology over the past few decades, it has been characterized by a wealth of ‘exploratory’ research with little hypothesis testing. It is well past the time to put more emphasis on the latter. I imagine there are ‘unknown unknowns’ awaiting discovery, but the larger problem is the lack of focus in resolving the ‘known unknowns’.

References

AlQuraishi, M., Sorger, P.K. Differentiable biology: using deep learning for biophysics-based and data-driven modeling of molecular mechanisms. Nat Methods 18, 1169–1180 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-021-01283-4

Anderson, C. The End of Theory: The Data Deluge Makes the Scientific Method Obsolete. Wired. 2008. https://www.wired.com/2008/06/pb-theory/

Buttigieg PL and Ramette A. 2014. A guide to statistical analysis in microbial ecology: a community-focused, living review of multivariate data analyses. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 90: 543–550, https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6941.12437

Calude CS and Longo G. 2017 The deluge of spurious correlations in big data. Found. Sci. 22: 595-612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10699-016-9489-4

Eren AM and Jillian F. Banfield JF. 2024. Modern microbiology: Embracing complexity through integration across scales. Cell 187: 5151-5170 2024

May RM. 2001. Stability and complexity in model ecosystems (Princeton landmarks in biology). Princeton University Press.

Nosek BA et al. (2018) The preregistration revolution. PNAS 115: 2600-2606. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1708274114

Platt JR. 1964. Strong Inference. Science 146: 347-353. DOI: 10.1126/science.146.3642.34

Prosser James I. 2020. Putting science back into microbial ecology: a question of approach Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 375:20190240. http://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0240

Succi S, Coveney PV. 2019. Big data: the end of the scientific method? Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 377: 20180145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2018.0145

Walsh C et al. 2023. Nine (not so simple) steps: a practical guide to using machine learning in microbial ecology. mBio 15: no. 2. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.02050-23

Today’s moment of Zen

The Great Mosque of Córdoba