I feel like my head is finally above water after a furious 4 weeks of moving pains. Entropy has been reduced in the new house to a level where I can once again Think Like a Microbe™️.

With regard to developing strategies to answer Big Questions in microbial ecology, I began with thoughts on sampling. Today I want to consider what technologies can be useful in this regard. And in the spirit of this substack, I am thinking particularly of technologies that allow analysis at the microenvironment scale.

Let’s begin with a quote from the father of modern microbial ecology, Robert Hungate (1971):

“The steps in analyzing a microbial ecosystem can be formulated as

(i) describing the kinds and numbers of organisms concerned,

(ii) identifying what they do, and

(iii) observing how fast they do it.

A complete description is kinetic, involving the rates of component processes and of the whole.”

The first step is exquisitely well-covered in modern work, particularly with respect to ‘kinds.’ The sequencing of 16S rDNA gene amplicons or the assembly of genomes from metagenomic sequencing has moved far beyond a cottage industry to become the dominant methodology in microbial ecology.

‘Identifying what they do’ (or more accurately, what they might do) can be ascertained from bioinformatic analysis of MAGs (metagenome-assembled genomes). But the mere presence of a gene (for example, nif for N2 fixation) does not mean the organism is actually carrying out the process – positive evidence would entail measuring either the activity itself, or transcription or translation of the gene (Konopka and Wilkins 2012).

‘How fast’ is the most difficult element, particularly if the measurement requires incubation of a natural sample in a separated container – the longer the incubation, the more process rates are likely to deviate from the in situ rate. Microelectrodes are the ideal device to interrogate microenvironments directly, as they can sense chemical gradients along one dimension for important chemical species such as O2, H+, H2, H2S, N2O, NO, as well as redox potential or temperature with spatial resolutions of 25 µm or less. But their utility is limited primarily to habitats such as microbial mats or organic-rich sediments that can be easily penetrated. A two-dimensional interrogation of sediments or soils can be carried out with planar optodes (Li et al., 2019) in which analyte-sensitive luminescent indicators are immobilized in a polymer matrix applied as a sheet to a face of the soil or sediment sample.

For much of the latter half of the 20th Century, radioisotopes of C, H, P and S were the most common means to assess microbial activities at near-in situ conditions. They certainly have confounding problems – the specific activity (Ci g-1) of particularly 14C organic compounds meant that it was very difficult to add them as “radiotracers,” that is, without altering the in situ concentration of the compound. My sense is that there has been a precipitous fall-off in the use of radioisotopes for activity measurements. To a certain degree, this has been supplanted by the use of stable isotopes of C, N, O and H. The bulk of this work has fallen under stable isotope probing (SIP; Radajewski et al., 2000), which typically says less about ‘how fast’ than identifying the responsible organisms via density gradient separation of isotopically heavy from light nucleic acids and subsequent analysis of 16S rDNA gene sequences. However, more recently, there have been very interesting developments using H218O in which the analyses are done quantitatively (qSIP), pioneered by the group at Northern Arizona University (Hungate et al., 2015). The output of this approach are taxon-specific growth rates, which represent a major advance over methods such as 3H-thymidine or 3H-leucine incorporation which produced an ‘average’ growth rate for the entire microbial assemblage (Foley et al., 2024).

Another intriguing 21st C technology for getting at the nature and consequences of microenvironments is the use of microfluidic devices. In the next edition of Think Like a Microbe, I’ll cover the strengths and weaknesses of using authentic natural samples vs constructed systems such as microfluidic devices. These devices offer advantages in replication of a structured microenvironment and also in systematically varying important structural properties (e.g., porosity and tortuosity) in habitats such as soil. One recently developed device is the RhizoChip, developed at the Environmental Molecular Sciences Lab at Pacific Northwest National Lab (Aufrecht et al., 2022).

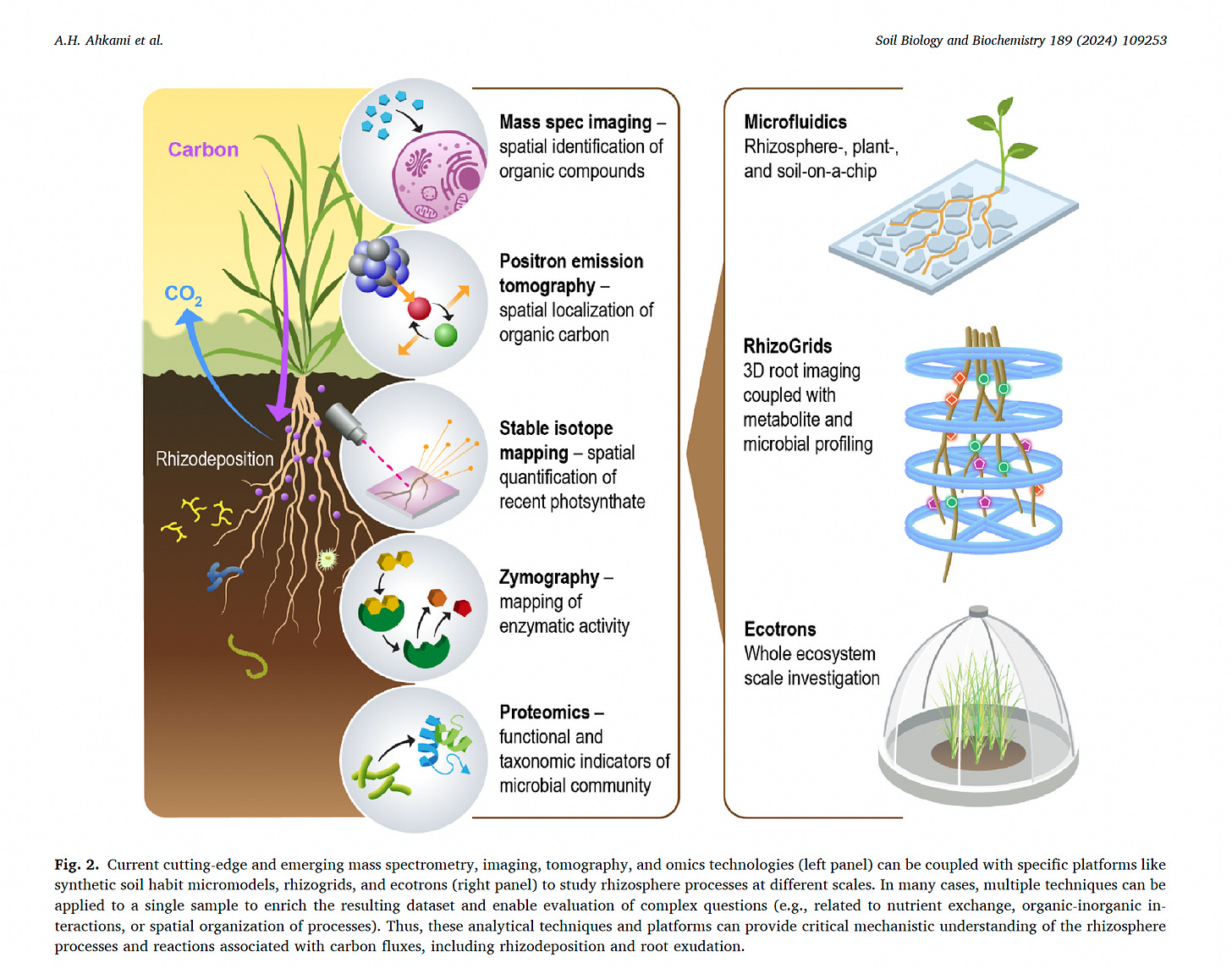

It represents just one piece of a suite of advanced technologies that can interrogate microbial processes in soil at a set of scales (Ahkami et al., 2024)

Why so much ‘who’s there?’ and so little ‘what are they doing?’?

My discussion of the technologies themselves has been abbreviated (and incomplete – see Hatzenpichler (2020) and Ahkami et al. (2024) for additional approaches). I want to delve into a philosophy of science / science of science question. There are now amazing means to get at the microscale where the interactions between microbes actually occur. Yet we see very little of them, in comparison to widespread sequencing of DNA retrieved from natural samples, which tells us a great deal about the ‘parts’ but very little about the ‘causings’. What might be the reasons behind that?

At the root of the explosion in nucleic acid sequence-based studies has been their broadly accessibility and relatively low expense. There are commercial kits for isolating DNA from environmental samples. Either the DNA itself or PCR amplicons of the 16S rDNA gene can be submitted to commercial or in-house sequencing centers. Of great importance here is that the cost of DNA sequencing has decreased more than 100,000-fold over the past 20 years. Whereas a small handful of sequences were analyzed from a sample in its early days, obtaining thousands of 16S rDNA gene sequences in a large number of samples is now routine.

Bioinformatic analysis of sequences is available from publicly-available resources such as QIIME2. Hence, the burdens of the most highly technical aspects (isolating and sequencing DNA + coding algorithms for sequence analysis) can be outsourced so that the investigator can concentrate on inferring meaning to the end product itself. As the kids say, this is a feature not a bug and has made this approach particularly powerful to implement.

Let’s contrast that with some of the technologies that can address microbial activities and microscale processes. NanoSIMS has been a powerful technique developed over the past 25 years. I found 85 publications (out of 1500 NanoSIMS citations on Web of Science (WoS)) that used this technique in a microbial ecology investigation. A key limiting factor here is accessibility – there are about 50 instruments worldwide (but not all are set up to analyze biological or environmental samples) and they require a highly trained and skilled operator. Raman microscopy also has some very interesting capacities to measure molecular or isotopic composition of individual cells (Hatzenpichler et al., 2020) but also suffers from the dearth of instruments and limited expert users.

A similar bottleneck may apply to the use of microfluidic devices to simulate natural microenvironments – a dedicated manufacturing facility with trained personnel is required. There have been about 180 publications over the past 20 years that have used this approach in microbial ecology. However, this is somewhat puzzling as a WoS search for microfluidics in microbiology more generally yielded 7000 publications over the same time interval, with a steady year-by-year increase. To systematically analyze the effects of spatial structure in heterogeneous environments such as soils, I am hard pressed to think of a better model than precision-engineered microfluidic devices.

On a more positive note, there has been a very encouraging increase in the number of publications employing transcriptomics in microbial ecology, from a few in the early 2000’s to >100 per year currently.

To conclude, there never has been a Golden Age for Hungate’s blueprint for analyzing microbial ecosystems. Nor have there ever been nascent technologies better equipped to interrogate the microscale environment of microbes and their individual properties. Substantial problems reside at the infrastructure and training levels and these are beyond the power of individual investigators to remedy. The question is whether funding agencies find these problems important enough to solve. Recall that the innovations in sequencing and analysis of microbial genomes were a happy consequence of the $3 Billion that US government agencies invested in the Human Genome Project. Is it conceivable within the well-developed research funding structures of countries in North America, Asia and Europe that a large, focused effort in analyzing how microbial ecosystems actually function would be deemed a worthwhile investment?

References

Aufrecht J et al. (2022) Hotspots of root-exuded amino acids are created within a rhizosphere-on-a-chip. Lab Chip. 22: 954-963. doi: 10.1039/d1lc00705j

Ahkami AH et al. (2024) Emerging sensing, imaging, and computational technologies to scale nano-to macroscale rhizosphere dynamics – Review and research perspectives. Soil Biol Biochem 189: 109253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2023.109253.

Foley MM et al. (2024) Growth rate as a link between microbial diversity and soil biogeochemistry. Nat Ecol Evol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02520-7

Hatzenpichler R et al. (2020) Next-generation physiology approaches to study microbiomefunction at single cell level. Nat Rev Microbiol 18:241-256. DOI 10.1038/s41579-020-0323-1

Hungate, BA et al. (2015) Quantitative Microbial Ecology through Stable Isotope Probing. Appl Environm Microbiol 81: 7570-7581

Hungate RE et al. (1971) Parameters of Rumen Fermentation in a Continuously Fed Sheep: Evidence of a Microbial Rumination Pool. Appl. Microbiol. 22:1104-1113

Konopka, A. and Wilkins, MW. (2012) Application of meta-transcriptomics and -proteomics to analysis of in situ physiological state. Front. Microbiol v3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2012.00184

Li, C. et al. (2019) Planar optode: A two-dimensional imaging technique for studying spatial-temporal dynamics of solutes in sediment and soil. Earth Sci Rev 197: 102916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2019.102916

Radajewski S et al. (2000) Stable-isotope probing as a tool in microbial ecology. Nature 403:646–649. https://doi.org/10.1038/35001054

Today’s moment of Zen

Monument Valley, AZ

Thank you for sharing this thread! I think this discussion is important and involves philosophical issues such as causal explanations concerning individuals and their interactions. It also goes further to conceptions and background assumptions regarding reductionism in its various forms, which allows (enables/legitimatizes) inferring actual microbial activity from potential activity implied by DNA.